Wiscasset And Quebec Railroad

The narrow gauge’s roots date back to the 1830’s, when the townspeople of Wiscasset, Maine wished to revive their dying seaport with a railroad connection, and when the state legislature was interested in establishing a railroad connection with Quebec. The Kennebec and Wiscasset Railroad was chartered in 1854 to build Wiscasset’s connection to other railroads. Little action was taken until the 1890’s when a few wealthy locals revived the dream and the Kennebec and Wiscasset’s successor, the Wiscasset and Quebec Railroad, was formed. It was decided that in order to save on construction and operation costs, the W&Q would be a two foot gauge road.

Construction began in June of 1894. Operations to Weeks Mills, 28 miles north of Wiscasset, began on February 20, 1895. Albion, 44 miles away and the end of the first leg to Quebec, was reached in November of that year. The company, in debt, paused in their push for Quebec at this point. Several years later, the second leg was started, but was halted due to a dispute in crossing the Maine Central tracks at Burnham Junction.

Settling down to business, the W&Q bought two brand new Portland Company Forneys, numbers 2 & 3, in 1894. Operations were sufficient to provide enough income to keep going, but the W&Q had accumulated a lot of debt during construction and afterwards. After several periods in receivership, it was bought out by a gentleman by name of Leonard Atwood, who reorganized the railroad into the Wiscasset, Waterville, and Farmington Railroad in 1901. The W&Q was dead for the time being.

Wiscasset, Waterville & Farmington Railroad

A north-bound train waits at the Wiscasset station for departure time. Photo from the E. Sproul collection.

While the WW&F dealt with operating in the Sheepscot Valley, the same Leonard Atwood chartered two companies to build to Farmington. The Franklin Construction Company would build from Weeks Mills to Waterville, while the Franklin, Somerset, and Kennebec would build from the Sandy River Railroad in Farmington and meet the branch from Weeks Mills. The FCC started building a bridge over the Kennebec River. The approaches were completed before the venture ran out of money, and the bridge was never finished. The railroad was built between Winslow and Weeks Mills, but the lack of the connection doomed the branch. The FS&K was stillborn from lack of interest by the SRRR and the Maine Central. Had the FS&K met up with the WW&F, it would have resulted in a huge 2-foot gauge empire, stretching from the mountains to the sea.

When the FCC presented the line to Winslow to the WW&F, they brought with them a brand new 28-ton Forney locomotive, which became #4. Four was a bit unusual, with a metal cab all around the tank, and slightly top-heavy, but excellent in snow plow duty. #4 was the engine in charge at the Mason’s Wreck, in 1905, and as a result was given a wooden cab afterward.

After ten years of operations, the railroad was deteriorating from lack of money to keep things in shape. Business was decent, as they were hauling lumber from the woods and coal to the American Woolen Company in Vassalboro, on the way to Winslow. They also had the mail contract and hauled passengers and many miscellaneous goods for the valley. However with their shaky past, they went into receivership in 1907, with the railroad being auctioned off to the highest bidder.

Wiscasset, Waterville & Farmington Railway

Help arrived in the form of Carson C. Peck, vice president of F.W. Woolworth Company, who paid the sum of $93,000 after spirited bidding. He reorganized the WW&F Railroad into the WW&F Railway, paying off all debts and establishing a capital improvement account in the bargain. Working closely with General Manager Sam Sewall, he authorized for any necessary improvements, including three new locomotives. Engine #5 arrived from the Bridgton and Saco River, and was a Hinckley Forney. Engines 6 & 7 were brand new Baldwins, and were the largest locomotives the road ever obtained. Six was a beautiful Prairie-type locomotive, similar to what the Sandy River had, and was built for freight hauling. Seven was a sleek and powerful passenger locomotive. Carson Peck’s administration was the best thing to come along for the impoverished railroad.

Business continued for the next 20 years. At the height of business, the road owned some 90 freight cars and 6 passenger cars, along with engines 1 through 7. Despite this, the railroad never became a big money-maker, but always made enough to stay in the black. Engine 1 was scrapped in 1913, as it was old (built in the 1880’s for the Sandy River), as was #5 from a burned crown sheet.

Agriculture was the primary business of the WW&F. Potatoes were an important commodity, as were poultry and lumber. The railroad also had the mail contract, and provided local children transportation to and from school in Wiscasset. The American Woolen Company was the Winslow branch’s biggest customer, until the Augusta, Lewiston and Waterville Street Railway (later the Androscoggin and Kennebec Railway) was built through Vassalboro and stole the coal contract. The Winslow branch was scrapped bits at a time until it was completely gone by the mid 1920’s.

Carson Peck died in 1915, passing the presidency to his wife Clara, and the actual management of the railroad to the Peck family attorney, Samuel Child. By the beginning of the 1920’s, the railroad was beginning to feel the pressure from cars and trucks taking business away bit by bit. The railroad continued to be profitable, but only at the expense of maintenance. The Peck family also wanted some return for their money, so they began demanding dividends in 1922. One of these dividend requests, in 1925, brought on the next financial crisis, and the railroad faced the scrappers. The road refinanced itself by offering common stock, which was actually purchased by some of the towns on the right of way. They bought out the Peck family for $50,000, and continued operation.

The Final Years

WW&F Engine #6 as she prepares to leave a station. Photo from the E. Sproul collection.

However, things were already slipping. Maintenance and business continued their downhill spiral, as potato farming left the Sheepscot Valley and trucks continued their inroads on business. In 1930, the WW&F was again faced with giving up, again went into receivership, and was once again saved, this time by Mr. Frank Winter, a businessman with lumber interests in Palermo. He completely bought up the railroad.

Mr. Winter’s main interest was keeping the lumber flowing, and maintenance was a low priority. In order to cut expenses in this era of the Great Depression, he fired just about everybody. However, in 1932, he began making improvement efforts, including buying two four-masted schooners (the Hesper and Luther Little) and stabilizing the Wiscasset wharf.

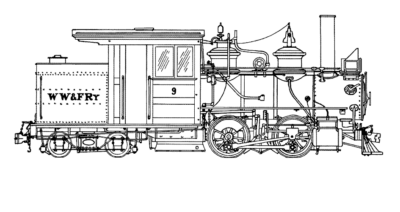

But things continued falling apart. Engines 6 and 7 burned in an enginehouse fire in 1931. Boiler inspectors told the railroad that their remaining locomotives, numbers 2, 3, and 4, would be condemned the next year. To solve this, Frank Winter bought the entire Kennebec Central Railroad, in Randolph, just for their two engines. Those engines became numbers 8 and 9. Both were Portland Forneys. Eight had originally come from the B&SR. Nine had started life as Sandy River #5, then SR&RL #6 before being sold to the KC.

Nine operated intermittently with the Three from early February, 1933, until June 13, 1933, when it was sidelined by a break in the rear frame. Eight operated for the next two days, until June 15, when on the down trip from Albion she jumped the track in Whitefield and nosed down the bank toward the Sheepscot river. The crew finished its run to Wiscasset using a motor railcar, but that was the last regular train on the Wiscasset, Waterville, and Farmington.

The mail contract was honored until October, with the “RPO” (Railway Post Office) operating out of an International panel truck. The railroad, however, sat idle for the next three years, until Frank Winter gave up on the idea of selling the line to someone, and decided to scrap it. Scrapping operations were slow and sporadic. Most of the mainline rail was ripped up in 1934 to satisfy unpaid bills. In 1937 the rolling stock was tipped over for the metal. The husks of Engines 2 through 7 were scrapped in Wiscasset Yard. Eight was cut up right where it had been left, and its pieces were hauled away.

The only exceptions to this destruction was Locomotive 9, Flatcar 118, Boxcars 309 and 312, a tip car, and Coach 3. Numbers 9, 118, 309, and a quarter mile of rail from the Kennebec Central Railroad were bought by a group of railfans. Today, everything except Boxcar 312 is now in the care of the WW&F Railway Museum.

Corporate History of the WW&F Railway

| COMPANY NAME | YEARS | PRESIDENTS | GENERAL MANAGERS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kennebec & Wiscasset Railroad Company | 1854 – 1873 | Henry Ingalls | |

| Wiscasset & Moosehead Lake Railroad Company | 1873 – 1876 | Henry Ingalls | |

| Wiscasset & Quebec Railroad Company | 1876 – 1893 | Henry Ingalls | |

| 1893 – 1894 | George Crosby | George Crosby | |

| 1894 – 1896 | Richard Rundlett | Richard Rundlett | |

| 1896 | Henry Ingalls | Fred Fogg | |

| 1896 – 1898 | (no president) | Fred Fogg | |

| 1898 | Albert Card | Godfrey Farley | |

| 1898 – 1900 | Godfrey Farley | Godfrey Farley | |

| Wiscasset & Quebec Railroad | 1900 – 1901 | Godfrey Farley | Godfrey Farley |

| Wiscasset, Waterville & Farmington Railroad Company | 1901 – 1904 | Leonard Atwood | Godfrey Farley |

| 1905 – 1907 | Godfrey Farley | Godfrey Farley | |

| Wiscasset, Waterville & Farmington Railway Company | 1907 – 1915 | Carson Peck | Sam Sewall |

| 1915 – 1925 | Clara Peck | Sam Sewall | |

| 1926 – 1929 | H. O. Phillips | Sam Sewall | |

| 1929 – 1930 | H. P. Crowell | H. P. Crowell | |

| 1930 – 1940 | Frank Winter | Frank Winter |

The Revival

The rolling stock bought by the group of railfans was stored on the farm of Frank Ramsdell of West Thompson, Connecticut. Locomotive 9 was kept in a shed, while the other pieces were outdoors. The plan was to build an amusement park. This never happened. The investors lost interest, and the pieces rested on the Ramsdell farm.

Frank’s daughter Alice Ramsdell inherited the farm upon her father’s death. Alice held on to the WW&F pieces — she absolutely would not sell, especially No. 9. She did allow tours of the property, however.

Meanwhile, back in Maine, WW&F owner Frank Winter still possessed the right of way and station buildings. The towns along the roadbed continued to tax him for these properties. Finally, to avoid many small but annoying property tax bills, he created the Winter Scientific Institutes and transferred ownership of the former railroad’s properties to that company. The Institutes administered the dispersal of the properties, although the land was remarkably slow to move. In 1985 the Institutes sold all the remaining property, most of which was bought up by one Harry Percival, Jr., of Alna.

This same Harry Percival had been working to restoring the road for many years. He struck up an acquaintance with Alice Ramsdell, even going so far as doing some preventative maintenance on the pieces (although he’d end up doing more farm work than rail work). Once he bought the right of way, he applied for a charter to start a corporation called the Wiscasset and Quebec Railroad, with a view to rebuilding a small portion of it. He received word back from the state that the W&Q had never been declared abandoned, and were he to hold a stockholder’s meeting he could get the corporation back in business. Thus, the original Wiscasset and Quebec Railroad corporation was back. In 1989 the Museum was formed, and thus continues the history of the WW&F Railway.